Dedicated and enthusiastic WEBINT Analyst with four years of experience. Multilingual with extensive research experience in online risk & fraud prevention in FinTech.

In recent years, in light of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, global economic sanctions have targeted Russian entities and individuals, aiming to curb their activities and financial reach to pressure their government to de-escalate war efforts. These sanctions were accompanied by decisions by private companies to suspend their activities partially or completely in Russia.

Western companies are leaving Russia in protest of the war, and to avoid any possible backlash against profits gained in Russia, which might be used to finance the latter’s war in Ukraine. But the withdrawal of Western brands also has massive political implications, serving as a greater reminder to ordinary Russians of their isolation than sanctions on Kremlin officials or central bank reserves.

In the context of financially motivated cybercrime, the most important of these companies are the major card networks (Mastercard, Visa, and American Express). The card networks have all announced that they will no longer allow Russian-issued payment cards to be used for transactions on their networks with merchants outside of Russia. Furthermore, major Russian banks were cut off from SWIFT, ceasing any transfers between the EU and Russia.

The sanctions have already shaken the Russian economy, leading to a sharp fall in the ruble and inflationary pressures. Russian-speaking threat actors have jumped on the opportunity to cater to this growing need to evade these sanctions.

There has been a rapid growth of fraudulent activities with the goal of satisfying the Russian consumer and creating an illusion of an intact world in Russia. With this in mind, since the major brand withdrawal and the first sanctions,

Cyberint noticed a growing trend of brand abuse, unauthorized resale, carding, and mule fraud, conducted by Russian threat actors. The Russian decision to legalize the so-called “parallel import,” only intensified the uptick in activity.

Parallel imports are goods that enter the market without the consent of the manufacturer: these are genuine products, but they may have been intentionally sold by the manufacturer in other countries.

For example, if branded clothes that were produced, packaged, and priced for the European market are imported by a distributor for sale in the US outside the clothing manufacturer’s certified sales channel, then this is a parallel import. Such imported products are considered gray market as they are sold by unauthorized resellers. However, since the brand owner has no control over the distribution of these items, they are not covered by the warranty program.

In May 2022, Russia launched a parallel import program, covering goods ranging from car parts, and electronics, to clothing, as imports plummeted. In May 2022, Russia published a list of Western goods that can be imported under the parallel import system. The list includes essentials such as warships, railway spares, and auto parts, as well as consumer goods such as electronics and household appliances, clothing, footwear, and cosmetics – goods that Russia says its Western manufacturers “refuse to supply directly”.

Russia even went so far, as to list specific brands that are eligible for this import scheme, such as Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, Continental, Ferrari, Apple, Samsung, Microsoft, Siemens, Duracell, Canon, PlayStation, and many others.

The Russian scheme protects importers from civil lawsuits for bypassing official distribution channels. Products now arriving in Russia are usually initially exported to countries that are part of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) led by Moscow, with which Moscow shares a customs union: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. These products are then shipped to Russia and sold on the market, with Western brands losing all control over their distribution and sales.

However, some goods are imported through detours to “friendly countries,” such as Iran, which has a visa-free entry agreement with Armenia, Turkey, the UAE, and so on. This means, that goods legally exported to a country to be sold there, might not have the same country as their end destination.

Parallel imports are generally not illegal. These are original licensed products that can only be purchased through parallel distribution channels, usually at a higher price. Russia’s plans include the international principle of copyright exhaustion, which allows Russian companies to import products without the manufacturer’s consent after they start selling in any country in the world. The main question is how carefully Western manufacturers will control sales of their products in foreign markets.

In the following chapter, we review some popular methods currently deployed by Russian threat actors using the parallel import scheme for the sake of sanctions evasion. However, although we divide the methods into categoriess, it should be noted that all these methods are rather aspects of the same scheme and can work separately or all together at the same time.

As mentioned previously, one of the most popular routes for parallel import is through “friendly” countries that continue to have an economic relationship with Russia. So, for example, the imports go through Kyrgyzstan, allowing the product to enter the Russian-operated customs union, before being trucked from Bishkek to Moscow, a journey that takes six days.

This Modus Operandi works for big retailers, but also for small businesses: Russian e-commerce platforms, such as Ozon and Wildberries, are building similar delivery lines on a larger scale and easing restrictions on sellers to meet Russian demand for Western goods.

Any Russian business that wants to buy goods in China, or any other country, must now open shell companies in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and other EAEU countries. Items are registered with these companies and payments are processed through them. The Russian client’s company is responsible for customs clearance and all logistics in the middleman country and pays the middleman company.

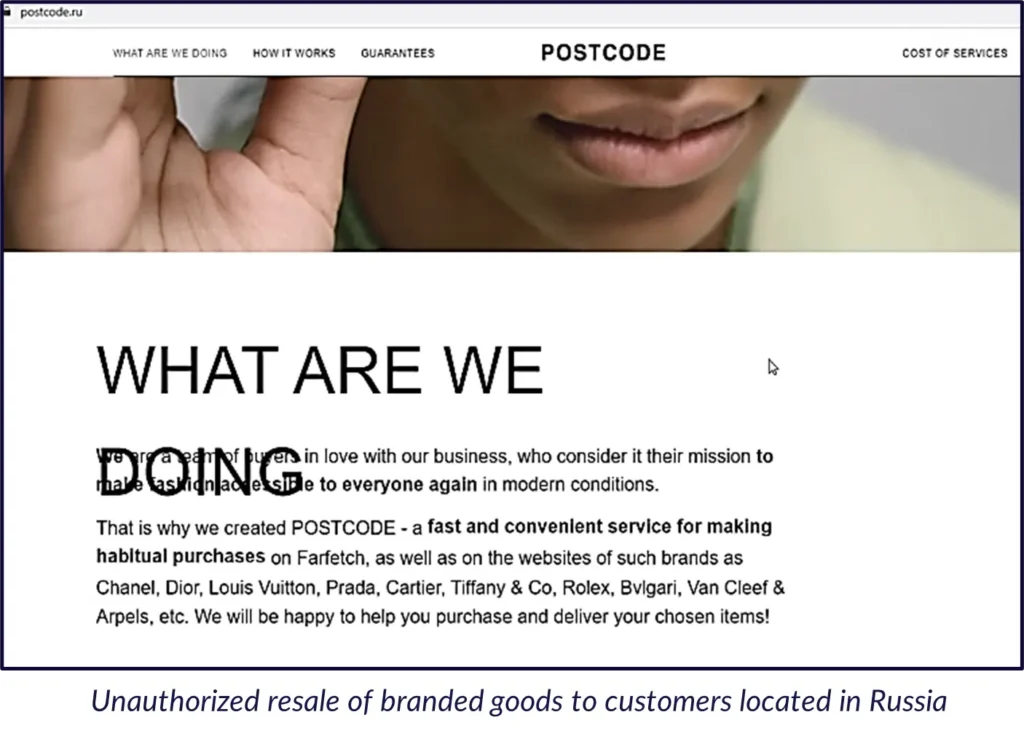

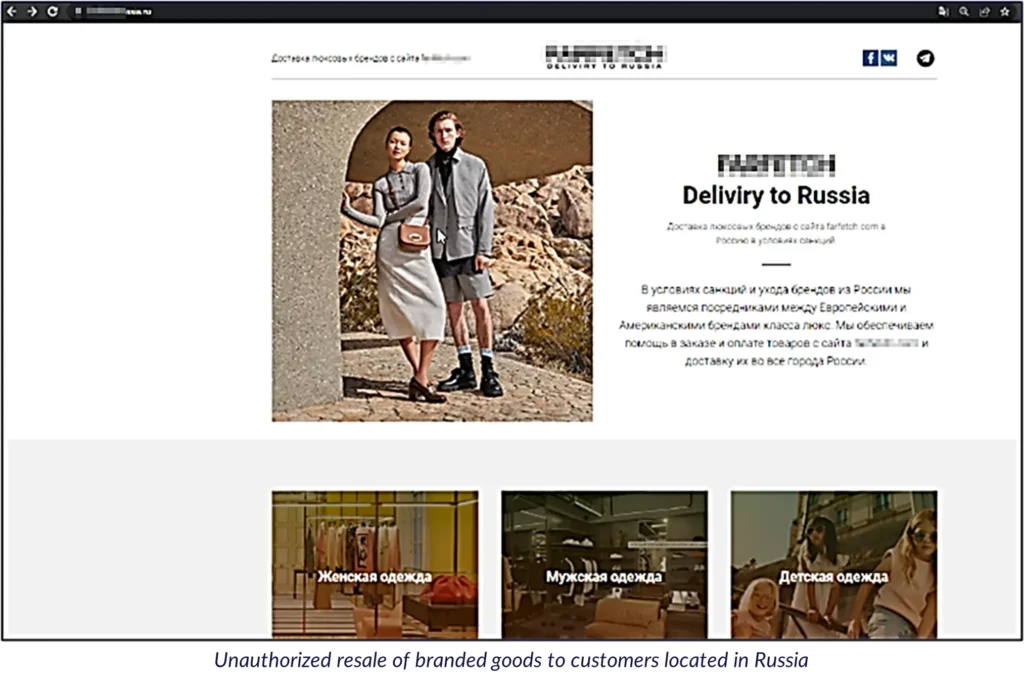

Example 1: An online store that sells branded products to customers located in Russia. The website refers to a telegram bot: the customer is instructed in Russian to look for desired items on the original brand website, then purchase them from telegram. The goods will be delivered to the desired address in Russia.

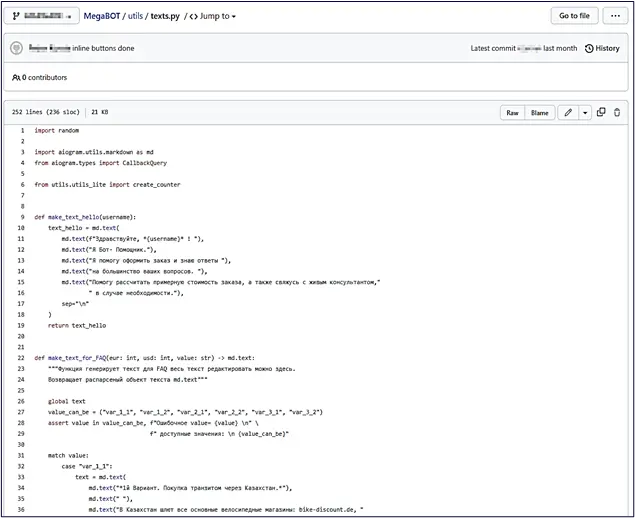

Example 2: A repository detected by Cyberint containing a custom chatbot script that can be used on a website serving customers located in the Russian Federation. It is supposed to help to navigate the delivery policy of certain European suppliers that would deliver their products to Kazakhstan, in this case without VAT.

Example 3: The online store offers their Russian customers the ability to order 1-3 products that are currently offered on the official branded website, by sending a link of the desired products together with their name, email address, phone number, and delivery address. Furthermore, the site’s delivery services accept money transactions from Sberbank (a Russian majority state-owned bank) and Tinkoff Bank (a Russian commercial bank), as well as crypto payments of Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Although many major shipping and freight companies announced that they would temporarily cease deliveries to Russia or only ship “essential goods”, threat actor networks, have been able to continue to reship goods to Russia, once again proving their adaptability.

Telegram is an extremely popular online messaging service in the CIS states and Russia. It can be counted as social media due to the option to create groups that other users can subscribe to. Most media and even governmental organizations in the CIS countries have Telegram groups and channels.

Messengers like Telegram have become one of the main platforms for parallel import: with sellers offering imported luxury goods and electronics, and even handling complex financial transactions, like transferring cash between Russia and the United States for a commission fee.

With western sanctions imposed on Russia, the decision by major global card networks to only allow transactions within Russia, and the exit of several internet service providers from Russia, create a new niche among the Russian threat actors in providing financial services for their co-nationals: from compromising payment cards, and monetizing cards, to various cashout schemes.

While threat actors engage in carding all around the world, Russia has historically seen a disproportionate number of threat actors engaged in carding. Russia has been a breeding ground for credit card fraud targeting victims around the world, with Russian threat actors compromising payment cards, operating darknet card markets, and monetizing compromised payment cards through various cashout schemes.

With major Russian banks cut off from SWIFT and heightened monitoring of EU bank accounts associated with Russian individuals, it is significantly more difficult for Western-based money mules to transfer funds to Russian banks.

To circumvent this problem, Russian dark web actors are turning to open bank accounts in nearby countries that do not impose sanctions on Russia, such as Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia. Threat actors can then use these bank accounts to profit from their network of money mules.

With cryptocurrency transfers, Russian users can still receive wallet payments, but due to currency controls imposed by the Russian government, they cannot convert funds into dollars, which is preferable to the currently volatile ruble. To circumvent this problem, dark web actors have started discussing the conversion of cryptocurrencies into hard currency through relatively unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges outside of Russia and the West, with exchanges in the same “friendly” countries that were mentioned in the report previously, such as Kazakhstan, Armenia, and others.

Threat actors often use mixing services and decentralized exchanges to further obscure the origins of their funds.

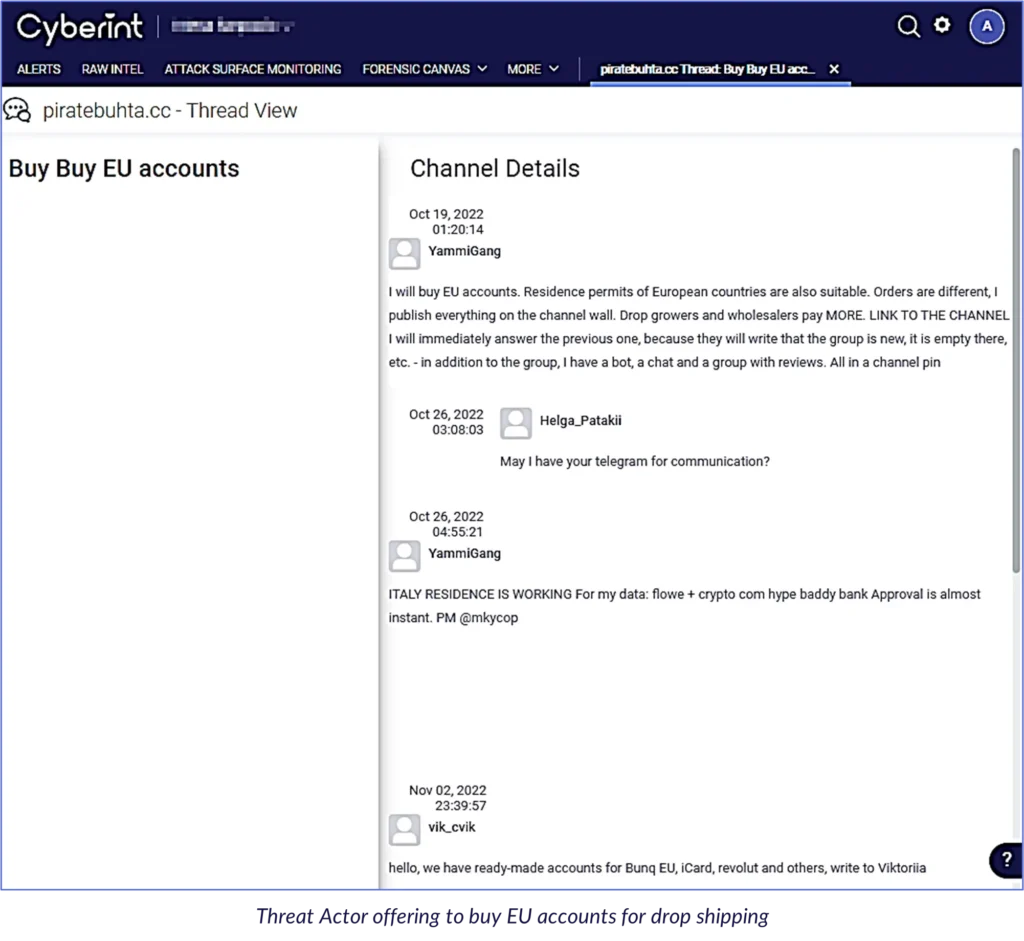

Example 6: In the screenshot below, taken from a darknet forum, a Russian threat actor is asking to purchase EU accounts for drop shipping. Additionally, the threat actor is looking for EU proof of residence documents, which could be used to interact with the said bank accounts for money laundering purposes. Mule accounts are often used for the initial part of money laundering, called placement. These types of accounts are used to transfer money to conceal the funds’ origin, which is often illegal. Should any individual associate his account with the mentioned inquiry, this could affiliate the account with malicious activity and potential money laundering.

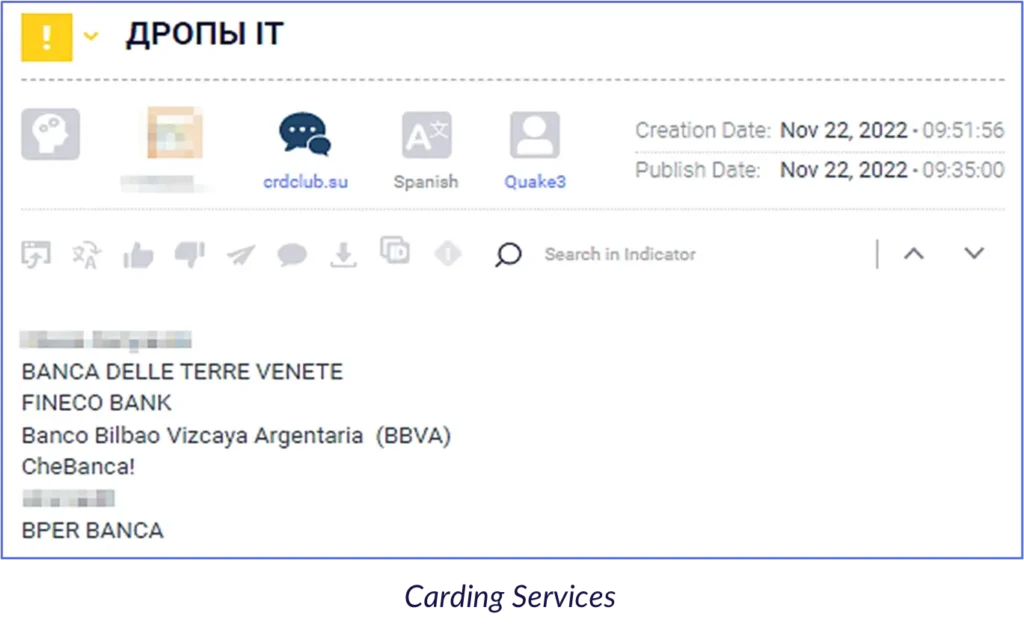

Example 7: A threat actor, on a Russian carding forum, claiming to hold “different drops”, most likely accounts for money laundering purposes. Furthermore, those that are interested can contact the threat actor to buy the “drops” and claim that he can verify the accounts through verification, expiration date, etc.

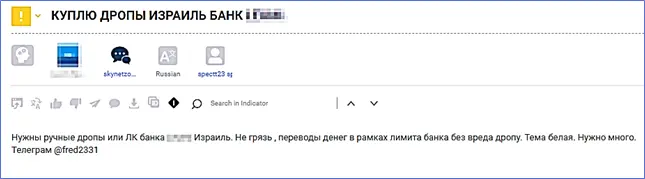

Example 9: A post in a darknet forum in which a threat actor was seeking to buy specific bank mule accounts. Cyberint contacted the threat actor in order to shed some light on the use of those mule accounts. The HUMINT operation was conducted via the threat actor’s Telegram account.

Russian-speaking threat actors need to maintain a steady supply of stolen credit card data and personal information to continue operating, hence the large demand of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) in the landscape. This data is often sold in bulk on dark web marketplaces. The increased availability of stolen data directly contributes to a rise in carding activities, where criminals use stolen card information to make authorized purchases.

In summary threat actors are implementing several ways to cicumvent the current sanctions:

Western companies may not be able to prevent parallel imports of their goods. Western governments may warn countries and companies not to help Russia circumvent sanctions or even threaten secondary sanctions. However, considering the EU’s proposal to make sanction evasion a criminal offense and therefore to put the responsibility on the manufacturers, some of them have begun to require their customers to prove they are physically not in Russia while placing an order.

Cyberint recommends reviewing orders to countries neighboring the Russian Federation that are used as popular routes for sanction evasion and identifying recipients that order in bulk and/or amount to more than €500. Those recipients are often the Russian third-party companies, that will organize the onward transportation of goods to customers in the Russian Federation.

Upon identification of a threat actor involved in parallel import, close monitoring is recommended. Furthermore, Cyberint can conduct a HUMINT investigation and contact the threat actor to try and shed light upon the scope of the operation.

Furthermore, for brand-abusing websites, involved in parallel import, Cyberint recommends the legal department of the affected companies report the domain to the registrar on trademark abuse claims. Once the registrar reclaims the ownership of the domain, it is advised to consider purchasing it in order to avoid future malicious activities at this site.

©1994–2025 Check Point Software Technologies Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright | Privacy Policy | Cookie Settings | Get the Latest News

Fill in your business email to start