As the fourth-largest economy worldwide, Japan stands as a pivotal center for various cutting-edge industries. This includes automotive, manufacturing, finance, and telecommunications, rendering its attack surface a prime target for cyber adversaries.

Japan’s Western alliances and its territorial dispute with Russia, alongside support for Ukraine, heighten its cyber threat profile from state actors like China, Russia, and North Korea.

In the protection of Japanese corporations, Cyberint evaluates the task of fortifying its cybersecurity infrastructure against the ongoing threat of cyber adversaries. The report incorporates our recommendations for mitigating and preventing substantial cyber risks.

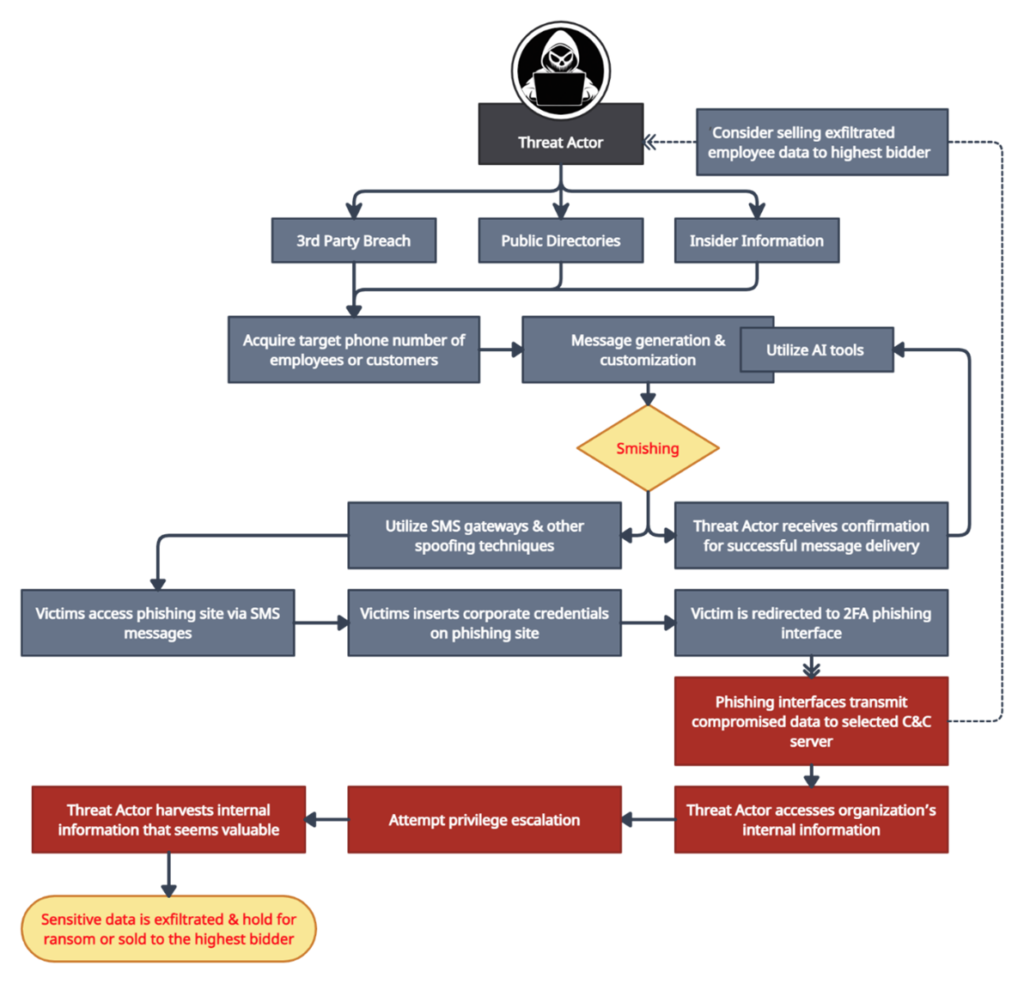

Phishing campaigns in Japan are prevalent cyber threats that target individuals, businesses, and organizations alike. These campaigns are orchestrated to deceive and manipulate victims, coercing them into divulging sensitive information, including personal credentials, financial data, or login credentials.

Within the field of social engineering attacks, a common strategy involves employing a sense of urgency by using certain keywords such as ‘urgent,’ ‘important,’ ‘invoice,’ purchase,’ and related triggers. These keywords have become widely recognized by spam filters employed in email services, thereby diminishing their effectiveness in that domain. However, it is worth noting that SMS inboxes typically offer lower levels of protection compared to email services, and have various vulnerabilities that organizations need to be aware of.

Such instances have been observed specifically targeting known organizations worldwide such as Twilio and Cloudflare. In these cases, SMS messages were crafted to deceive employees into believing they needed immediate action or attention. Consequently, the employees were redirected to deceptive phishing interfaces, exposing them to potential security breaches.

While phishing vectors are the most common method for smishing, they can also be utilized to distribute malware without the victim’s knowledge. This poses a significant concern, particularly when corporate interfaces are accessible on personal mobile devices, such as Microsoft Outlook or VPNs, which may be susceptible to 0-day vulnerabilities.

Japan’s relatively high level of digitization makes it an attractive target for threat actors leveraging generative AI products for several reasons.

Generative AI offers threat actors a versatile toolset for various nefarious activities, including automated vulnerability discovery, which can significantly enhance the cost-effectiveness of attacks.

Moreover, AI facilitates threat actors in both the planning and execution stages of their campaigns, empowering them to tailor attack materials to suit multiple potential targets.

In the past year, Cyberint witnessed multiple cases of weaponization of AI by Threat Actors. Models like WormGPT, WolfGPT, and FraudGPT and others were created by malicious actors. They are primarily used to craft intricate computer worms and malware, exploit system vulnerabilities, generate persuasive and deceptive content for fake news articles and social media posts, or produce counterfeit documents, fake identities, and aid in phishing attempts.

Moreover, in recent years, threat actors have increasingly targeted foreign subsidiaries over Japanese headquarters due to the ease of conducting social engineering attacks and reconnaissance in English. However, advancements in AI translation and crafting capabilities may soon break down this language barrier and alter this dynamic.

In March of 2024 the IT equipment and services company Fujitsu, reported that they have suffered a cyber-attack.

In an online statement, the company claimed that they have confirmed the presence of malware on several work computers. The computers contained sensitive files and information that could be illegally taken out using the malware. The company also said that following the discovery they have informed the relevant authorities and disconnected the infected machine immediately. The incident is still under investigation and officials from Fujitsu are investigating whether any information was leaked.

In October of 2023, Japanese tech giant LY Corporation, has disclosed it suffered a breach of hundreds of thousands of individuals via a Line messaging app data breach.

The breach contained 440,000 items of personal data, including users’ age group, gender, and partial service usage histories. The Line app data breach exposed approximately 86,000 business partners’ data items, including email addresses, names, and affiliations, as well as over 51,000 employee records with ID numbers and email addresses. An investigation revealed that hackers accessed the data by breaching a South Korea-based affiliate, NAVER Cloud, through malware on a subcontractor’s computer. The attack likely exploited a shared personnel management system with common authentication.

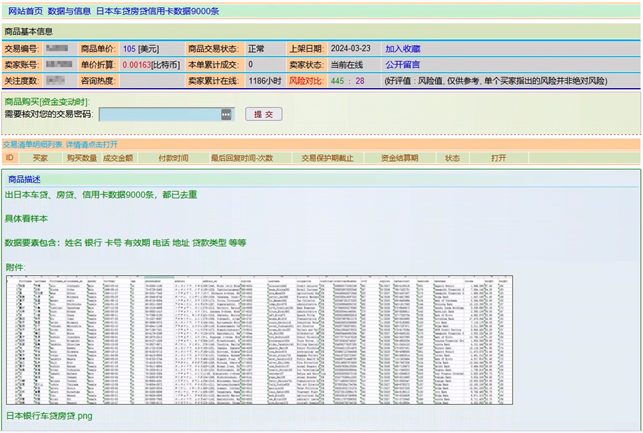

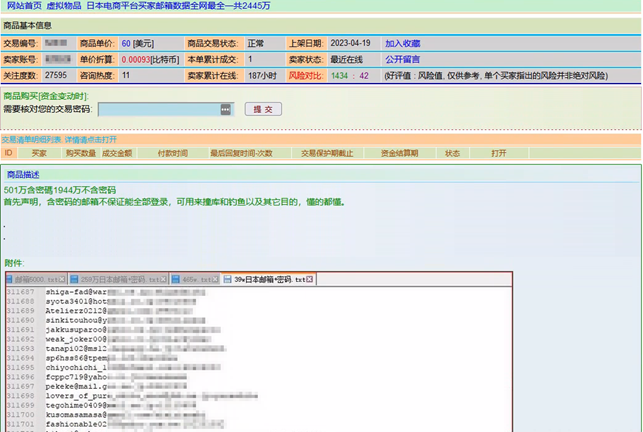

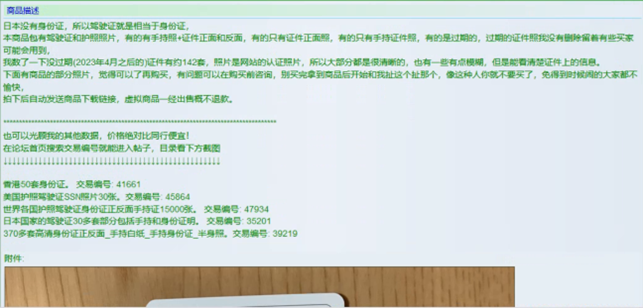

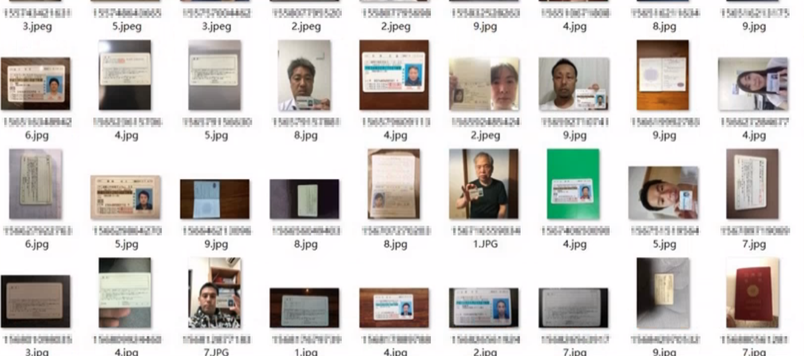

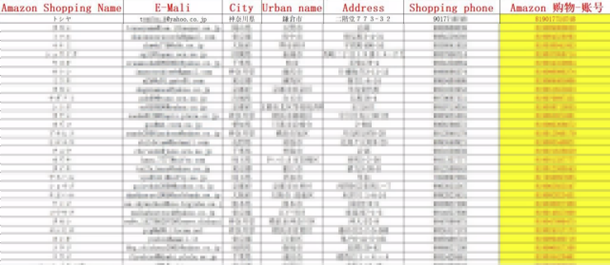

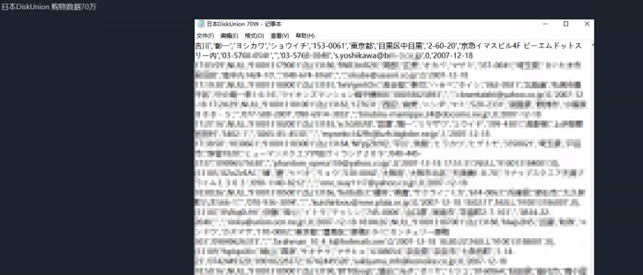

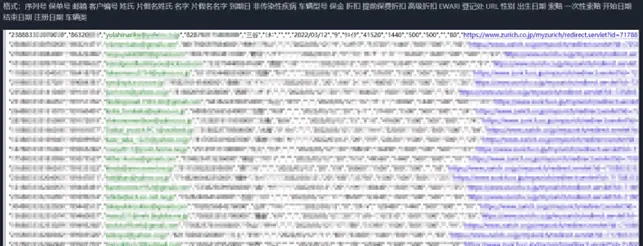

In recent years, there has been a notable trend of Japanese data circulating within English-speaking underground forums. However, Cyberint monitoring and analysis indicate a distinct surge in interest within the Chinese-speaking dark web community regarding breaches concerning Japanese data.

Amidst regional tensions, Chinese-speaking threat actors are showing a heightened interest in compromising and trading stolen data from Japanese corporations and individuals alike.

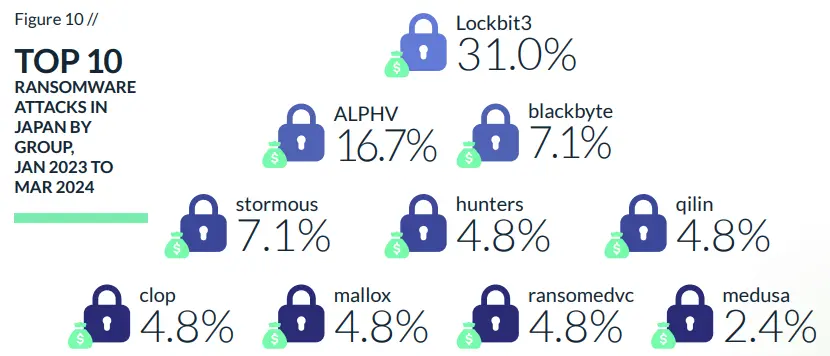

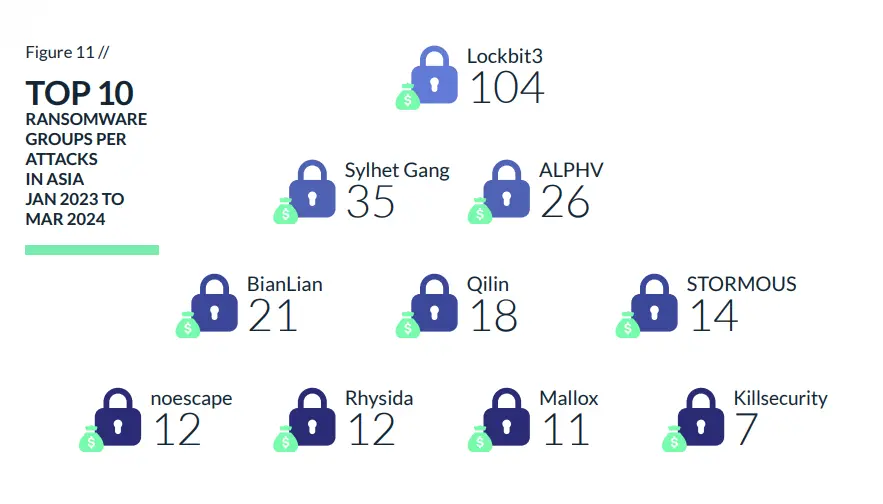

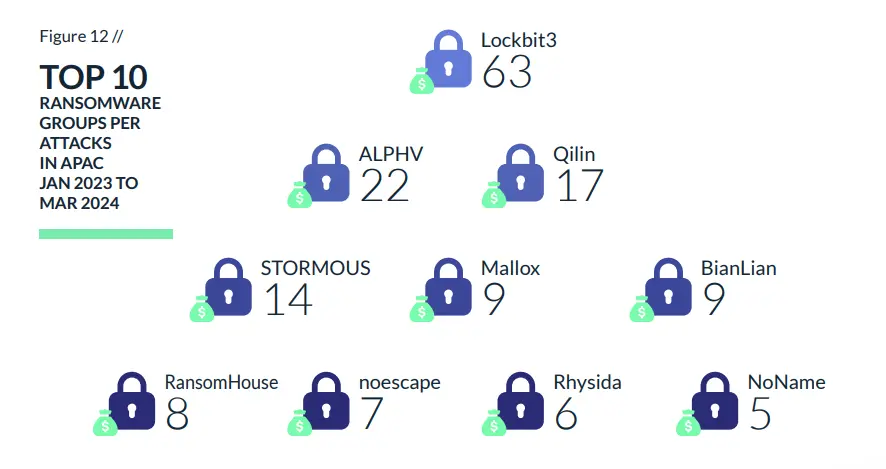

Japanese businesses rank as the second most targeted ransomware victims in Asia. Ransomware attacks have a profound impact on organizations, particularly in Japan, which boasts one of the world’s most robust hubs for automotive, technology, manufacturing finance and telecommunications. Ransom attacks in the region predominantly target the manufacturing industry. Financial losses are a major consequence, encompassing ransom payments, incident response costs, and potential legal actions. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often struggle to recover due to limited resources.

Operational disruption is another significant repercussion, affecting critical systems and causing downtime, delayed services, and customer dissatisfaction. Data loss, including sensitive business data and customer information, can lead to legal issues, damage trust, and result in financial penalties. Additionally, ransomware attacks inflict reputational damage, resulting in customer loss, decreased brand value, and challenges in acquiring new business. Rebuilding trust and restoring reputation require substantial time and effort.

Below are several charts outlining key statistics on ransomware attacks impacting Japan and the broader region, alongside a glimpse into some of the ransomware groups involved.

LockBit ransomware has been linked to a higher number of cyberattacks this year compared to any other ransomware, establishing itself as the most active ransomware globally. LockBit initially surfaced in September 2019 and has since undergone evolution: transitioning from LockBit 2.0 in 2021 to its current iteration, LockBit 3.0.

LockBit seeks initial access to target networks primarily through purchased access, unpatched vulnerabilities, insider access, and zero-day exploits. “Second-stage” LockBit establishes control of a victim’s system, collects network information, and achieves primary goals such as stealing and encrypting data.

LockBit attacks typically employ a double extortion tactic to encourage victims to pay, first, to regain access to their encrypted files and then to pay again to prevent their stolen data from being posted publicly. When used as a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS), an Initial Access Broker (IAB) deploys first-stage malware or otherwise gains access within a target organization’s infrastructure. They then sell that access to the primary LockBit operator for second-stage exploitation.

LockBit 3.0 seeks initial access to target networks primarily through purchased access, unpatched vulnerabilities, insider access, and zero-day exploits. In LockBit’s RaaS model, the primary operating group recruits Initial Access Brokers (IAB) through advertisements on the dark web to obtain stolen credentials for Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) or Virtual Private Network (VPN) access. The LockBit group also develops exploits for known software vulnerabilities to take advantage of unpatched or misconfigured enterprise networks.

After initial access is gained, LockBit 3.0 malware downloads C2 tools appropriate for the target environment. LockBit 3.0’s second-stage C2 malware uses standard penetration testing tools such as Cobalt Strike Beacon, MetaSploit, and Mimikatz, as well as custom exploit code. Like Conti, LockBit 3.0 can spread within a target network using worm-like functionality. LockBit 3.0 malware source code is also notorious for protecting itself from analysis by security researchers; tools are encrypted by default and only decrypted when a suitable environment has been detected.

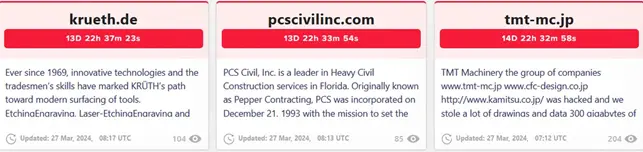

In March 2024, TMT Machinery announced that a third-part vendor had access to their internal systems and encrypted some sensitive Data. Accordingly, on March 27th LockBit posted their name on their Dark-web website. TMT Machinery conducted an investigation and released a statement claiming that they have not yet paid the ransom and that, aside from a few screenshots lacking sensitive information, no data has been posted online.

File Sharing Sites:

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| IP | 212[.]102[.]39[.]138 |

| IP | 194[.]32[.]122[.]35 |

| IP | 178[.]175[.]129[.]35 |

| IP | 178[.]162[.]209[.]138 |

| IP | 178[.]162[.]209[.]137 |

| IP | 172[.]93[.]181[.]238 |

| IP | 156[.]146[.]41[.]94 |

| IP | 216[.]24[.]213[.]7 |

| IP | 37[.]46[.]115[.]29 |

| IP | 37[.]46[.]115[.]26 |

| IP | 37[.]46[.]115[.]24 |

| IP | 37[.]46[.]115[.]17 |

| IP | 37[.]46[.]115[.]16 |

| IP | 212[.]102[.]35[.]149 |

| IP | 178[.]175[.]129[.]37 |

| IP | 91[.]90[.]122[.]24 |

| SHA256 | 5fff24d4e24b54ac51a129982be591aa59664c888dd9fc9f26da7b226c55d835 |

| SHA256 | bb574434925e26514b0daf56b45163e4c32b5fc52a1484854b315f40fd8ff8d2 |

| SHA256 | 9a3bf7ba676bf2f66b794f6cf27f8617f298caa4ccf2ac1ecdcbbef260306194 |

| SHA1 | e141562aab9268faa4aba10f58052a16b471988a |

| SHA1 | 3d62d29b8752da696caa9331f307e067bc371231 |

| SHA1 | 3d62d29b8752da696caa9331f307e067bc371231 |

| MD5 | 03f82d8305ddda058a362c780fe0bc68 |

| MD5 | fd8246314ccc8f8796aead2d7cbb02b1 |

| MD5 | f41fb69ac4fccbfc7912b225c0cac59d |

| MD5 | ee397c171fc936211c56d200acc4f7f2 |

| MD5 | dfa65c7aa3ff8e292e68ddfd2caf2cea |

| MD5 | d1d579306a4ddf79a2e7827f1625581c |

| MD5 | b806e9cb1b0f2b8a467e4d1932f9c4f4 |

| MD5 | 8ff5296c345c0901711d84f6708cf85f |

| MD5 | 8af476e24db8d3cd76b2d8d3d889bb5c |

| MD5 | 6c247131d04bd615cfac45bf9fbd36cf |

| MD5 | 58ea3da8c75afc13ae1ff668855a63 |

ALPHV, also known as BlackCat, is a significant ransomware group, operating through Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) with global affiliates. ALPHV is highly adaptable and predominantly targets large entities like corporations and organizations. It ranks among the top three ransomware groups, with origins traceable back to DarkSide, notorious for the Colonial Pipeline Incident. Moreover, it has been observed recruiting former REvil members.

When observing ALPHV’s activity, the group mainly focuses on the business services sector and the Manufacturing industry. In addition, most of their activity is taking place in the United States followed by Canada.

The ransom is distributed through Cobalt Strike or a similar framework. Those behind BlackCat utilize LOLBins and custom scripts to navigate through networks and gather information about the environment.

The initial stage of ALPHV attacks relies on phished, brute-forced, or illicitly obtained credentials, often targeting Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) connections and Virtual Private Network (VPN) services, along with exploiting vulnerabilities like CVE-2019-7481.

The subsequent phase of a ALPHV attack typically involves establishing reverse SSH tunnels to a ALPHV -controlled command-and-control (C2) infrastructure. Once connected, the attacks are entirely command-line driven, managed by humans, and highly customizable. The primary goal of ALPHV post-infection is to move laterally within the victim’s network, using tools like PsExec to target Active Directory user and administrator accounts, and to exfiltrate and encrypt sensitive files.

The main payload of ALPHV is the first known malware written in the “Rust” programming language, capable of infecting both Windows and Linux-based systems. ALPHV is effective against various versions of Windows, including XP and later (including Windows 11), Windows Server versions from 2008 onwards, Debian and Ubuntu Linux, ESXI virtualization hypervisor, as well as ReadyNAS and Synology network-attached storage products.

While ALPHV primarily focuses on targets in the US, Canada, and the UK, some Japanese businesses have also fallen victim to their attacks. On Mar 01, 2024, Kumagai Gumi was compromised by the threat actor group. Kumagai Gumi is a Japanese construction company founded in Fukui, Fukui Prefecture, Japan. The compromised data allegedly amounts to 5 TB.

Moreover, ALPHV has targeted in Novemebr 2023 Japan Aviation Electronics Industry and in August 2023 the well-known Japanese watch manufacturer Seiko.

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| MD5 | 09bc47d7bc5e40d40d9729cec5e39d73 |

| MD5 | 173c4085c23080d9fb19280cc507d28d |

| MD5 | 20855475d20d252dda21287264a6d860 |

| MD5 | 6c2874169fdfb30846fe7ffe34635bdb |

| MD5 | 6c6c46bdac6713c94debbd454d34efd9 |

| MD5 | 815bb1b0c5f0f35f064c55a1b640fca5 |

| MD5 | 817f4bf0b4d0fc327fdfc21efacddaee |

| MD5 | 82db4c04f5dcda3bfcd75357adf98228 |

| MD5 | 84e3b5fe3863d25bb72e25b10760e861 |

| MD5 | 861738dd15eb7fb50568f0e39a69e107 |

| MD5 | 91625f7f5d590534949ebe08cc728380 |

| MD5 | 9f2309285e8a8471fce7330fcade8619 |

| MD5 | 9f60dd752e7692a2f5c758de4eab3e6f |

| MD5 | a3cb3b02a683275f7e0a0f8a9a5c9e07 |

| MD5 | e7ee8ea6fb7530d1d904cdb2d9745899 |

| MD5 | f5ef5142f044b94ac5010fd883c09aa7 |

| MD5 | fcf3a6eeb9f836315954dae03459716d |

| SHA1 | 1b2a30776df64fbd7299bd588e21573891dcecbe |

| SHA1 | 37178dfaccbc371a04133d26a55127cf4d4382f8 |

| SHA1 | 3f85f03d33b9fe25bcfac611182da4ab7f06a442 |

| SHA1 | 4831c1b113df21360ef68c450b5fca278d08fae2 |

| SHA1 | 8917af3878fa49fe4ec930230b881ff0ae8d19c9 |

| SHA1 | a186c08d3d10885ebb129b1a0d8ea0da056fc362 |

| SHA1 | bf1b0ab5a2c49bde5b5dbe828df3e69af5d724c2 |

| SHA1 | d241df7b9d2ec0b8194751cd5ce153e27cc40fa4 |

| SHA1 | fce13da5592e9e120777d82d27e06ed2b44918cf |

| SHA256 | 31eb1de7e840a342fd468e558e5ab627bcb4c542a8fe01aec4d5ba01d539a0fc |

| SHA256 | 3c300726a6cdd8a39230f0775ea726c2d42838ac7ff53bfdd7c58d28df4182d5 |

| SHA256 | 731adcf2d7fb61a8335e23dbee2436249e5d5753977ec465754c6b699e9bf161 |

| SHA256 | 80dd44226f60ba5403745ba9d18490eb8ca12dbc9be0a317dd2b692ec041da28 |

| SHA256 | F837f1cd60e9941aa60f7be50a8f2aaaac380f560db8ee001408f35c1b7a97cb |

Hunters International is a ransomware collective that came to the spotlight in October 2023. It has been determined that the first victim was featured on their website on October 20, 2023.

Researchers have asserted that Hunters International’s ransomware demonstrates technical similarities with approximately 60% of the Hive ransomware codebase. These identified parallels with Hive indicate a potential evolutionary relationship or a derivative of the previously dismantled group.

The threat actors responded to the allegations by denying affiliation with Hive claiming that they had simply purchased the group’s source code, which was being offered for sale. They further claimed that they had fixed certain issues within the code, inadvertently causing decryption unavailability in some cases.

Hunters International is a ransomware group that specifically targets Windows and Linux environments. Upon completing data exfiltration, the group appends a “LOCKED” extension to the encrypted files on the compromised system. Their operations have a global reach and impact a wide array of sectors, including health, automotive, manufacturing, logistics, finance, education, and food.

A ransomware attack perpetrated by Hunters International targeted Hoya Corporation, demanding a payment of $10 million in exchange for a file decryptor and to prevent the compromised stolen files from being disclosed.

Hoya is a Japanese company specializing in optical instruments, medical equipment, and electronic components. It operates 160 offices and subsidiaries in more than 30 countries and a network of 43 laboratories worldwide.

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| SHA256 | c4d39db132b92514085fe269db90511484b7abe4620286f6b0a30aa475f64c3e |

First appearing in September 2021, BlackByte acquired the reputation of a poorly coded ransomware, according to experts. Furthermore, the cybersecurity firm Trustwave discovered a vulnerability and used it to develop a free decrypter. The threat actors generally target industries in the energy, agriculture, financial services, and public sectors.

According to some experts, Blackbyte utilizes a range of tools and techniques to plant their ransomware. The threat actor’s modus operandi includes exploiting unpatched Microsoft Exchange Servers, deploying web shells for remote access, using living-off-the-land tools for persistence and reconnaissance, and employing Cobalt Strike beacons for command and control. They evade defenses through process hollowing and vulnerable drivers, ensure persistence with custom-developed backdoors, and utilize a specialized tool for data collection and exfiltration.

The Blackbyte ransomware group targets organizations worldwide, including multiple businesses in Japan. One of the companies they targeted is the U.S. offices of Yamaha Corporation, a leading Japanese manufacturer of musical instruments and audio equipment. The group announced on June 14, 2023 that they had breached the company. Subsequently, on July 21 2023, another ransomware group called Akira added the company to its leaks list.

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| IP | 185.93.6.31 |

| IP | 45.9.148.114 |

| MD5 | 4d2da36174633565f3dd5ed6dc5033c4 |

| MD5 | eed7357ab8d2fe31ea3dbcf3f9b7ec74 |

| MD5 | 0c7b8da133799dd72d0dbe3ea012031e |

| MD5 | 28b791746c97c0c04dcbfe0954e7173b |

| MD5 | b8e24e6436f6bed17757d011780e87b9 |

| MD5 | c010d1326689b95a3d8106f75003427c |

| MD5 | 11e35160fc4efabd0a3bd7a7c6afc91b |

| MD5 | 959a7df5c465fcd963a641d87c18a565 |

| MD5 | 51f2cf541f004d3c1fa8b0f94c89914a |

| MD5 | cea6be26d81a8ff3db0d9da666cd0f8f |

| MD5 | a9cf6dce244ad9afd8ca92820b9c11b9 |

| MD5 | ad29212716d0b074d976ad7e33b8f35f |

| MD5 | d2a15e76a4bfa7eb007a07fc8738edfb |

| MD5 | cd7034692d8f29f9146deb3641de7986 |

| MD5 | 695e343b81a7b0208cbae33e11f7044c |

| MD5 | a77899602387665cddb6a0f021184a2b |

| MD5 | 52b8ae74406e2f52fd81c8458647acd8 |

| MD5 | 8dfa48e56fc3a6a2272771e708cdb4d2 |

| MD5 | ae6fbc60ba9c0f3a0fef72aeffcd3dc7 |

| MD5 | 659b77f88288b4874b5abe41ed36380d |

| MD5 | 5f40e1859053b70df9c0753d327f2cee |

| MD5 | d9e94f076d175ace80f211ea298fa46e |

| MD5 | 31f818372fa07d1fd158c91510b6a077 |

| MD5 | 7139415fecd716bec6d38d2004176f5d |

| MD5 | d4aa276a7fbe8dcd858174eeacbb26ce |

| MD5 | e46bfbdf1031ea5a383040d0aa598d45 |

| MD5 | d63a7756bfdcd2be6c755bf288a92c8b |

| MD5 | 296c51eb03e70808304b5f0e050f4f94 |

| MD5 | 1473c91e9c0588f92928bed0ebf5e0f4 |

| MD5 | 1785f4058c78ae3dd030808212ae3b04 |

| MD5 | 4ce0bdd2d4303bf77611b8b34c7d2883 |

| MD5 | 405cb8b1e55bb2a50f2ef3e7c2b28496 |

| MD5 | 151c6f04aeff0e00c54929f25328f6f7 |

| MD5 | df7befc8cdc3c5434ef27cc669fb1e4b |

| MD5 | 8320d9ec2eab7f5ff49186b2e630a15f |

| MD5 | d9e94f076d175ace80f211ea298fa46e |

| MD5 | c13bf39e2f8bf49c9754de7fb1396a33 |

| MD5 | 58e8043876f2f302fbc98d00c270778b |

| MD5 | 5c0a549ae45d9abe54ab662e53c484e2 |

| MD5 | 9344afc63753cd5e2ee0ff9aed43dc56 |

| MD5 | e2eb5b57a8765856be897b4f6dadca18 |

| SHA-1 | f3574a47570cccebb1c502287e21218277ffc589 |

| SHA-1 | ee1fa399ace734c33b77c62b6fb010219580448f |

| SHA-1 | c90f32fd0fd4eefe752b7b3f7ebfbc7bd9092b16 |

| SHA-256 | e837f252af30cc222a1bce815e609a7354e1f9c814baefbb5d45e32a10563759 |

| SHA-256 | 1df11bc19aa52b623bdf15380e3fded56d8eb6fb7b53a2240779864b1a6474ad |

| SHA-256 | 91f8592c7e8a3091273f0ccbfe34b2586c5998f7de63130050cb8ed36b4eec3e |

In general, the Eastern Asia region witnesses a notable presence of state-sponsored advanced persistent groups, ranging from major North Korean and Russian APTs to others associated with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

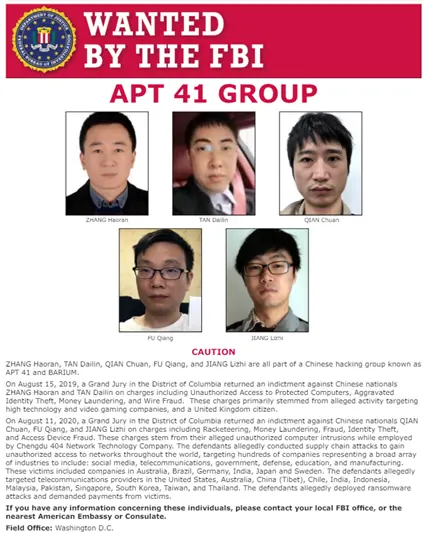

Given its geopolitical positioning and strategic alliances with entities such as QUAD and NATO, Japan has been a target for several APTs, including APT10, APT41, APT29, Fancy Bear and Lazarus Group, and may continue to be under scrutiny by prominent APT groups in the region. Provided below is a brief overview into three of the most pertinent APTs.

Operating since 2006, APT10 is a cyberespionage group affiliated with the Chinese government, potentially linked to the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS). In 2018, the group gained notoriety for infiltrating and pilfering trade secrets and technologies from at least 12 countries. Various security agencies refer to APT10 using different monikers such as MenuPass (FireEye), Stone Panda (CrowdStrike), APT10 (Mandiant), and POTASSIUM (Microsoft).

In an unusual move for an APT group, APT10 was observed employing ransomware attacks as a decoy to mask its malicious activities in June 2022.

APT10 employs a mix of traditional and modern attack methods, including spear-phishing and supply chain attacks. Since 2009, the group has used LNK files and files with double extensions in spear-phishing attacks. Notably, starting in 2017, APT10 initiated hacking through global service providers, leveraging sophisticated supply chain attacks to access victims’ networks.

The group employs DLL hijacking/side-loading, process hollowing techniques, and has utilized trending flaws like ProxyLogon and ProxyShell in Exchange Servers. A significant deviation was observed around mid-2022 when APT10 used ransomware as a decoy to conceal espionage-related activities.

APT10 utilizes a variety of malware, including information stealers like ScanBox, RATs such as Quasar, PlugX, P8RAT, and PoisonIvy, as well as backdoors like BugJuice (RedLeaves), SodaMaster, Hartip, SnuGride, HayMaker, and Uppercut. Loaders like HUI Loader, Ecipekac, FYAnti, and trojans like Impacket.AI and ChChes are also part of their arsenal. Additionally, ransomware strains like Rook, Pandora, AtomSilo, LockFile, and Night Sky have been attributed to APT10. APT10 employs a diverse set of tools, including AdFind, certutil, Cobalt Strike, Ecipekac, esentutl, Mimikatz, PsExec, PowerSploit, Wevtutil, tcping, Ntdsutil, Csvde, and pwdump.

APT10 is strongly linked to Chinese state agencies, aligning its operations with Chinese national interests. The group was involved in cyberattacks during the 2018 Olympics, and code fragments in the Olympic Destroyer malware were traced back to APT10. Intrusion Truth, in September, reported APT10’s association with the Chinese intelligence agency, particularly China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS). Two Chinese individuals, Zhu Hua and Zhang Shilong, were charged in 2018 for breaking into the networks of over 45 technology firms and U.S. government agencies, revealing further ties to APT10.

In 2020, Symantec uncovered APT10’s campaign targeting Japanese organizations. In April 2022, APT10’s activities intersected with another threat group named TA410, using an upgraded version of malware called JollyFrog, further suggesting a connection between the two.

Between 2022 and 2024, APT10 launched attacks on Japanese targets, primarily political institutions, using phishing emails bearing LODEINFO Fileless Malware. Over time, and especially in 2023, this malware evolved through multiple iterations, incorporating sophisticated remote code execution and detection evasion techniques.

Like other Chinese espionage factions, the targeting strategies of APT41 align predominantly with China’s Five-Year economic development plans. This group has effectively established and maintained strategic access to organizations operating within the healthcare, high-tech, and telecommunications sectors. Although APT41 primarily focuses on financially motivated activities within the video game industry, they have also exhibited operations targeting higher education, travel services, and news/media firms, suggesting a broader surveillance agenda.

APT41’s financial pursuits within the video game industry include manipulating virtual currencies and even attempting ransomware deployment. The group demonstrates proficiency in navigating targeted networks, seamlessly transitioning between Windows and Linux systems to gain access to game production environments. Subsequently, they pilfer source code and digital certificates, utilizing the latter to sign malware. Furthermore, APT41 leverages its access to production environments to inject malicious code into legitimate files, later distributed to unsuspecting victim organizations. These supply chain compromise tactics are indicative of APT41’s prominent espionage campaigns.

Interestingly, despite the complexity and scale of supply chain compromises, APT41 restricts the deployment of follow-on malware to specific victim systems by meticulously matching individual system identifiers. This multi-stage approach not only ensures targeted malware delivery but also conceals the true scope of their intended victims, a departure from conventional spear-phishing campaigns that often reveal targets based on email addresses.

APT41 employs sophisticated techniques, notably in financially motivated activities such as software supply-chain compromises. By injecting code into legitimate files, they pose a significant threat to organizations, stealing data and manipulating systems. Utilizing advanced malware, including boot kits, facilitates data extraction without detection.

Their utilization of Lowkey malware and the Deadeye launcher underscores their adeptness at immediate reconnaissance while evading detection. Spear-phishing emails are frequently employed for both cyberespionage and financial endeavors, often tailored to high-level targets using acquired personal information.

According to reports from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, APT41 leverages a variety of software tools for malicious activities:

| IP | C&C Domains |

|---|---|

| 45.142.214.242 | delaylink[.]tk, javaupdate.biguserup[.]workers.dev |

| 45.153.231.31 | |

| 45.144.31.31 | colunm[.]tk |

| 45.142.214.56 | mute-pond-371d.zalocdn[.]workers.dev, cs16.dns04[.]com |

| 45.140.146.169 | gentle-voice-65e3.bsnl[.]workers.dev, newimages.socialpt2021[.]tk, updata.microsoft-api[.]workers.dev |

| 45.142.212.47 | socialpt2021[.]club, mute-pond-371d.zalocdn[.]workers.dev |

| 185.250.150.22 | mute-pond-371d.zalocdn[.]workers.dev |

| 45.133.216.21 | |

| 45.153.231.32 | |

| 185.118.166.66 | colunm[.]tk |

The Lazarus Group, recognized by numerous aliases such as Hidden Cobra, Zinc, APT-C-26, Guardians of Peace, Group 77, Who Is Hacking Team, Stardust Chollima, and Nickel Academy, operates under the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB) of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). In 2017, a joint technical alert (TA17-164A) issued by the U.S. government, based on analyses by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), identified Hidden Cobra as a “North Korean state-sponsored malicious cyber organization.”

The Lazarus Group’s activities align closely with North Korea’s political interests, with South Korea and the U.S. serving as primary targets. However, the group extends its operations to other countries, including Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Guatemala, Hong Kong, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.

Operating on a broader scale than other nation-state threat actors, Lazarus Group’s objectives encompass information theft, financial extortion, espionage, sabotage, and disruption. In addition to engaging in bank robberies, cryptocurrency theft, and ransomware attacks for financial gain, the group selectively targets sectors such as energy, aviation, and defense to acquire strategically significant intelligence.

The Lazarus Group has refined its strategy over time, transitioning from initial DDoS operations against diverse organizations to employing a more destructive arsenal of malware and TTPs.

While the group’s attack patterns may vary, they typically follow similar procedures. Lazarus Group meticulously plans sophisticated attacks, conducting thorough reconnaissance on potential victims to ascertain vulnerabilities and optimal attack timings.

Utilizing techniques like spear phishing, supply-chain attacks, waterhole attacks, and zero-day vulnerability exploitation, Lazarus Group gains access to targeted networks and maintains persistence through custom-built malware such as remote access trojans (RATs), backdoors, and botnets.

To evade detection and cover their tracks, Lazarus Group deletes logs and data, deploying malware or ransomware when necessary. In the event of detection, the group acts swiftly to avoid forensic investigations by promptly repackaging malware and altering encryption keys and algorithms.

Known for their aggressive tactics, including employing disk-wiping malware, Lazarus Group focuses on disruption, sabotage, financial theft, and espionage activities. They continuously develop and modify custom malware for operations, utilizing a range of tools including backdoors (Appleseed, HardRain, BadCall, Hidden Cobra, Destroyer, Duuzer), RATs (Fallchill, Joanap, Brambul), and the notorious ransomware Wannacry.

In their attacks, Lazarus Group leverages both zero-day vulnerabilities and known exploits, including vulnerabilities in Adobe Flash Player, Microsoft Office, South Korean local software (e.g., Hangul Word Processor), and the SWIFT financial software.

Lazarus Group crypto Ethereum address:

IoCs of Wannacry

| Hash Type | Hash Value |

|---|---|

| MD5 | 5a89aac6c8259abbba2fa2ad3fcefc6e |

| MD5 | 05da32043b1e3a147de634c550f1954d |

| MD5 | 8e97637474ab77441ae5add3f3325753 |

| MD5 | c9ede1054fef33720f9fa97f5e8abe49 |

| MD5 | f9cee5e75b7f1298aece9145ea80a1d2 |

| MD5 | 638f9235d038a0a001d5ea7f5c5dc4ae |

| MD5 | 80a2af99fd990567869e9cf4039edf73 |

| MD5 | c39ed6f52aaa31ae0301c591802da24b |

| MD5 | db349b97c37d22f5ea1d1841e3c89eb4 |

| MD5 | f9992dfb56a9c6c20eb727e6a26b0172 |

| MD5 | 46d140a0eb13582852b5f778bb20cf0e |

| MD5 | 5bef35496fcbdbe841c82f4d1ab8b7c2 |

| MD5 | 3c6375f586a49fc12a4de9328174f0c1 |

| MD5 | 246c2781b88f58bc6b0da24ec71dd028 |

| MD5 | b7f7ad4970506e8547e0f493c80ba441 |

| MD5 | 2b4e8612d9f8cdcf520a8b2e42779ffa |

| MD5 | c61256583c6569ac13a136bfd440ca09 |

| MD5 | 31dab68b11824153b4c975399df0354f |

| MD5 | 54a116ff80df6e6031059fc3036464df |

| MD5 | d6114ba5f10ad67a4131ab72531f02da |

| MD5 | 05a00c320754934782ec5dec1d5c0476 |

| MD5 | f107a717f76f4f910ae9cb4dc5290594 |

| MD5 | 7f7ccaa16fb15eb1c7399d422f8363e8 |

| MD5 | 84c82835a5d21bbcf75a61706d8ab549 |

| MD5 | bec0b7aff4b107edd5b9276721137651 |

| MD5 | 86721e64ffbd69aa6944b9672bcabb6d |

| MD5 | 509c41ec97bb81b0567b059aa2f50fe8 |

| MD5 | 8db349b97c37d22f5ea1d1841e3c89eb |

| SHA1 | 6fbb0aabe992b3bda8a9b1ecd68ea13b668f232e |

| SHA256 | 0a73291ab5607aef7db23863cf8e72f55bcb3c273bb47f00edf011515aeb5894 |

| SHA256 | 21ed253b796f63b9e95b4e426a82303dfac5bf8062bfe669995bde2208b360fd |

| SHA256 | 228780c8cff9044b2e48f0e92163bd78cc6df37839fe70a54ed631d3b6d826d5 |

| SHA256 | 2372862afaa8e8720bc46f93cb27a9b12646a7cbc952cc732b8f5df7aebb2450 |

| SHA256 | 2ca2d550e603d74dedda03156023135b38da3630cb014e3d00b1263358c5f00d |

| SHA256 | 3ecc7b1ee872b45b534c9132c72d3523d2a1576ffd5763fd3c23afa79cf1f5f9 |

| SHA256 | 43d1ef55c9d33472a5532de5bbe814fefa5205297653201c30fdc91b8f21a0ed |

| SHA256 | 49fa2e0131340da29c564d25779c0cafb550da549fae65880a6b22d45ea2067f |

| SHA256 | 4a468603fdcb7a2eb5770705898cf9ef37aade532a7964642ecd705a74794b79 |

| SHA256 | 616e60f031b6e7c4f99c216d120e8b38763b3fafd9ac4387ed0533b15df23420 |

| SHA256 | 66334f10cb494b2d58219fa6d1c683f2dbcfc1fb0af9d1e75d49a67e5d057fc5 |

| SHA256 | 8b52f88f50a6a254280a0023cf4dc289bd82c441e648613c0c2bb9a618223604 |