The online gaming realm is evidently a lucrative plateau for hackers to milk sensitive data out of emphatic game players and the virality that accompanies their hype.

But what is it that attracts cybercriminals to the ‘gametime’?

We were at Casual Connect San Francisco last week, and walking around the trade show, I wouldn’t say that it was easy to spot physical cyber criminals roaming around, but their presence was still “in the vibes”.

When looking through the hackers’ lens, it’s easy to identify what it is about trends in online gaming that lures in the criminal mind.

Points of weakness within databases, intellectual property, and online communities — are all obvious opportunities for a hacker’s entry, and he knows it more than anybody else.

And when gaming trends reach their viral point of existence (think: Clash of Kings, Pokemon Go, and the like) — it won’t be long until he jumps on the bandwagon.

And who gets the raw end of this deal?

Not only the victimized customers — the brand, the developers, everyone goes home in shame; their brand sentiment is tarnished, their online communities may very well be broken, and well, their revenues may also hit a heavy blow.

The hacker thinks of everything: fake coupons for games, in-game cash…once he knows what the players are after, he’ll make sure to get it to them.

[Read Now: Phishing, Facebook, And The Enterprise: The Love Triangle That Hurts Us Most]

High-octane databases full of user credentials, Facebook access tokens, and so on, what more could a hacker ask for?

Game virality means players relish in an “on-demand” system. If their game happens on a mobile app, they’re giving that app everything they can to score higher. No matter what the app asks for, the user will throw it in there, the privacy policies are of little importance once his hands hit the touch screen.

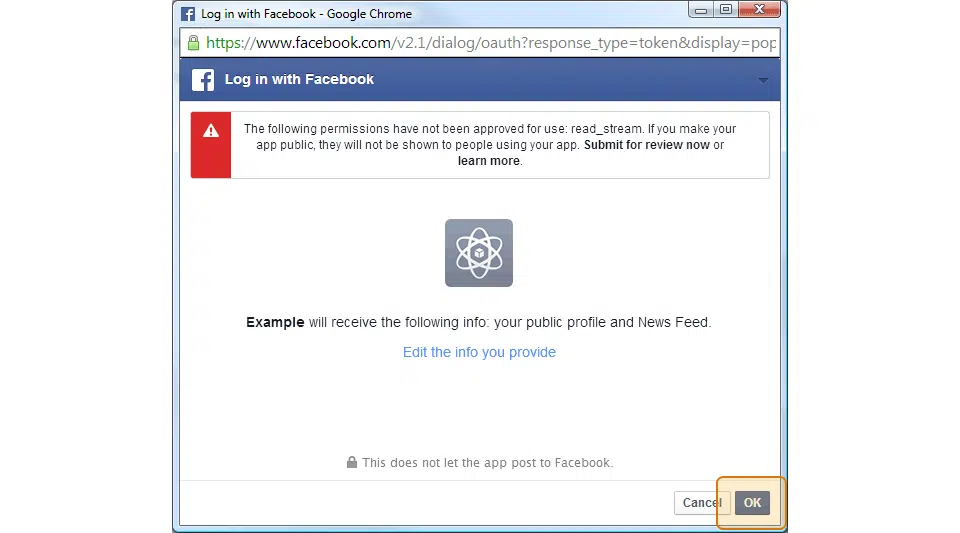

And well, if the game is on Facebook, which is becoming man’s go-to habitat for social interactions and for information sources, he’s no longer thinking about protecting himself and his assets. He’s a free-spirited traveler around the network, and is quick to submit details and personal credentials into his intuitive, trusted surroundings and interfaces.

When virality meets (either) natural habitats or a funzone, hackers will get there, and ASAP.

Once a hacker reaches a user’s Facebook data, he can potentially reach any site or subscription which the user logged into/subscribed to through Facebook; e-commerce sites, online subscriptions, etc.

This is precisely the opportunity that was grabbed this week around the “Clash of Kings” player community. Once a “Clash of Kings” activist logs into the game through Facebook (which is very often the case), his array of credentials and sensitive data become the hacker’s prey.

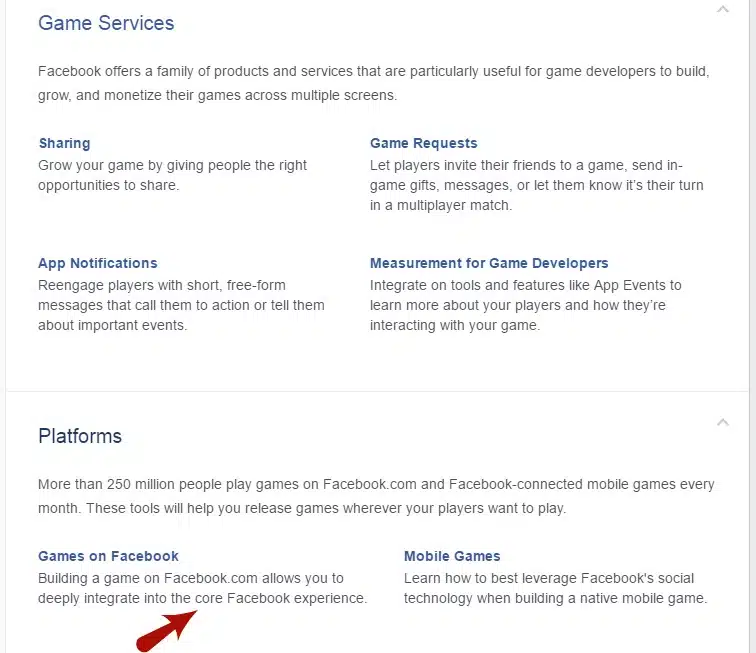

The Facebook Game platform does indeed grow opportunities for developers, brands, and well, customers, too — as they show on the Facebook developers’ site, shown below:

True, building a game on Facebook does make game playing a lot easier, accessible for players — which makes it easier for the brand to turn its players into (brand) evangelists. It’s seemingly a win-win.

On a good day, both developers and game players benefit from a game like “Clash of Kings” — gaming communities are boundless avenues of growth and player collaboration; traction and publicity become easy peasy for the brand, and growth is prosperous in all directions.

But we left one growth factor out; this game hype is viral, and on these crowded, populated online forums, hackers sniff the opportunity to pursue their criminal goals.

In the case of “Clash of Kings”, the (undisclosed, at least for now) hacker found two (easy to exploit) vulnerabilities:

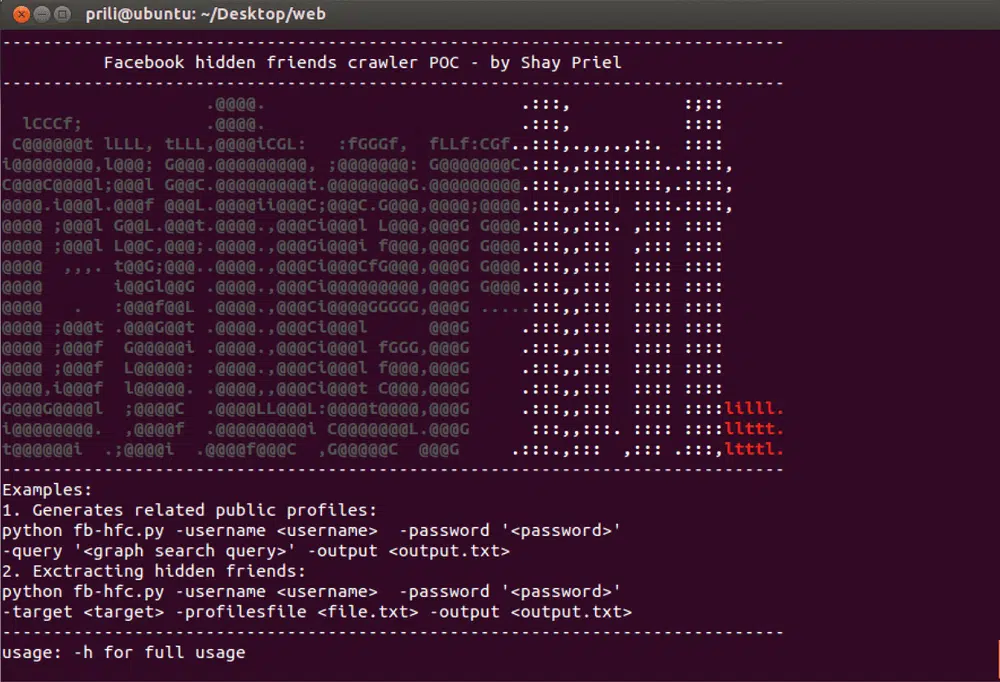

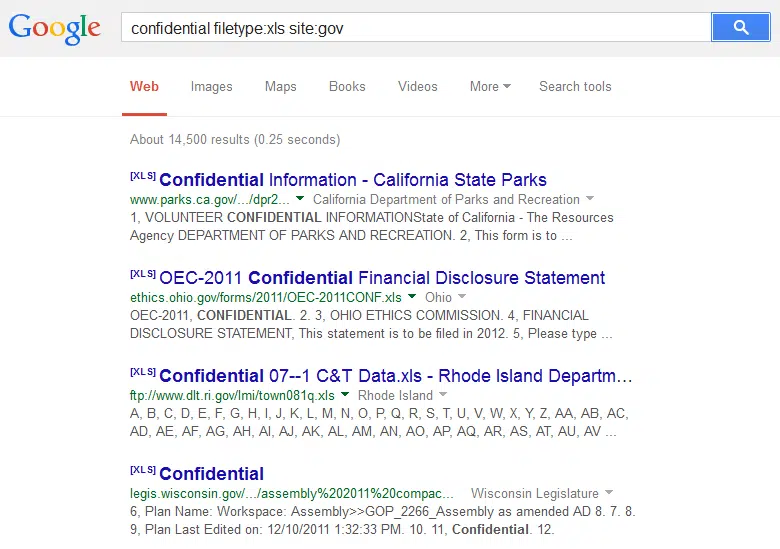

In this particular case, the hacker used the “Google dorking” technique — where cyber criminals actively seek out (via search engines) sites that run out-of-date forum software, with insecure configuration.

He’s reached the forum, then what?

Once the hacker reaches a database like the one on vBulletin, he’s gotten his hands on plenty: usernames, email addresses, IP addresses (which may very well determine the user’s location), device identifiers, Facebook data, and access tokens.

You know the rest: 1,597,717 user profiles later, the happy cyber criminal comes home happy: with a full-on smorgasbord of personal credentials.

And if only the damage would stop there…

Last week, just before “Clash of Kings” suffered it’s ugly collision with the hackers, Venture Beat framed the possibility of hacking Pokemon Go as “a classic case of follow the money”, and The Daily Beast labeled it “a hacker’s dream”, as they explain:

“To play it, you have to give up your most private information. It’s only a matter of time, experts say, before that data is in hackers’ hands. While you’re out collecting Pokemon on your phone this week, a Google spinoff company will be busy collecting data about you.”

True, Pikachu can be found anywhere this summer: beaches, amusement parks, office buildings, school buildings, university campuses, and so on.

But you don’t need to find Pikachu in a school setting to teach him all he needs to know. You just have to play it once.

On Android devices, for example, Pokemon Go players (via the Niantic-based app) must submit the following: date of birth, and access to your camera, contacts, GPS location, and SD card contacts, to name a few.

And you can’t play the game without active WiFi or GPS signal, so there’s no getting past the info stage. It’s all or nothing.

The data breaches that lie in the scope of Pokemon Go actually have the potential to be worse than usual. What’s unique about Pokemon Go’s intellectual property system is that Niantic, the app provider that Pokemon Go operates on, has a unique privacy policy — complicated for game players, and well, attractive to cyber criminals.

Their policy has become known to offer “scant details” of how they handle their data, and where they store it; Niantic are even qualified to hand PII (personally-identifiable information) over to law enforcement bodies, “who are able to then sell it off, share it with third parties, and even store it in foreign countries with lax privacy legislation.”

Whether brands are dedicating time and money into aligning their game with the Facebook platform, or they’re making sure to fall back on an ‘opportune’ PII system, these investments only last so long.

Once a hacker gets in their way, the data is lost, the customers follow, and the brand, well, it probably doesn’t look so good.

It’s no coincidence. Although it feels as real as ever (it is virtual reality, after all), Pokemon Go and “Clash of Kings” are, at the end of the day, each an imaginary game.

But the outcomes are far from anyone’s imagination, they’re as real as ever.

©1994–2025 Check Point Software Technologies Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright | Privacy Policy | Cookie Settings | Get the Latest News

Fill in your business email to start