Highly motivated, problem solver, dot connector, energetic multi-dimensional & professional management with commercially oriented, customer service skills & PMO abilities in high-growth, fast-paced organizations.

Subscriptions-based services are a reality we all are getting used to; most people no longer buy physical media for example, opting to use streaming services for movies and music. This has numerous advantages like letting us explore new artists and genres without additional costs and commitment. Yet, while best known for its implementation in the digital world, subscription payment models are slowly but surely being adopted by more and more industries.

In the car industry, Volvo and Porsche are two early adopters of note that started offering subscription plans over the past several years, allowing users to try out different models across their range, with all costs such routine services included. However, recent trends indicate that the automotive industry subscription plans resemble more to microtransaction models. Features and capabilities are design to be only available with the purchase of a relatively small fee. In essence, placing features that previously were seen as solely pay-to-own, and more critically tied to the basic functionality of the product, behind a paywall.

In late November Toyota tried to quietly introduce its plans to make its car key fob remote start feature into a subscription service. Although not the first time a similar program was made by an automotive company, it is possibly the first from a major mainstream manufacturer, which is far more likely to impact others. An aspect easily overlooked is the potential risk they may pose to industries’ operation if maliciously exploited.

As stated, subscription services aren’t new to the automotive world, but until now were mostly limited to luxury brands. BMW, for instance, considered additional charge for Apple CarPlay apps in their vehicles, and Mercedes made its electric cars’ rear-wheel steering in Europe a paid option. Tesla too is no stranger to this concept, going so far as to as to disable – allegedly by mistake – Autopilot driver assistance features from a used Model S.

But, in this iteration the subscription plan resembles more like a “microtransaction” program that hamstrings basic functionalities, rather than enabling customers to pay for arguably nice-to-have and/or premium features, worryingly taking after the gaming industry. While the remote start option on its own does not initially seem like a crucial function to many, it’s not hard to see how introducing a potently on-mass disable function to cars’ ignition operation is alarming – be it due to accident or to malicious intent – especially, when it come from one of the world’s largest car manufactures.

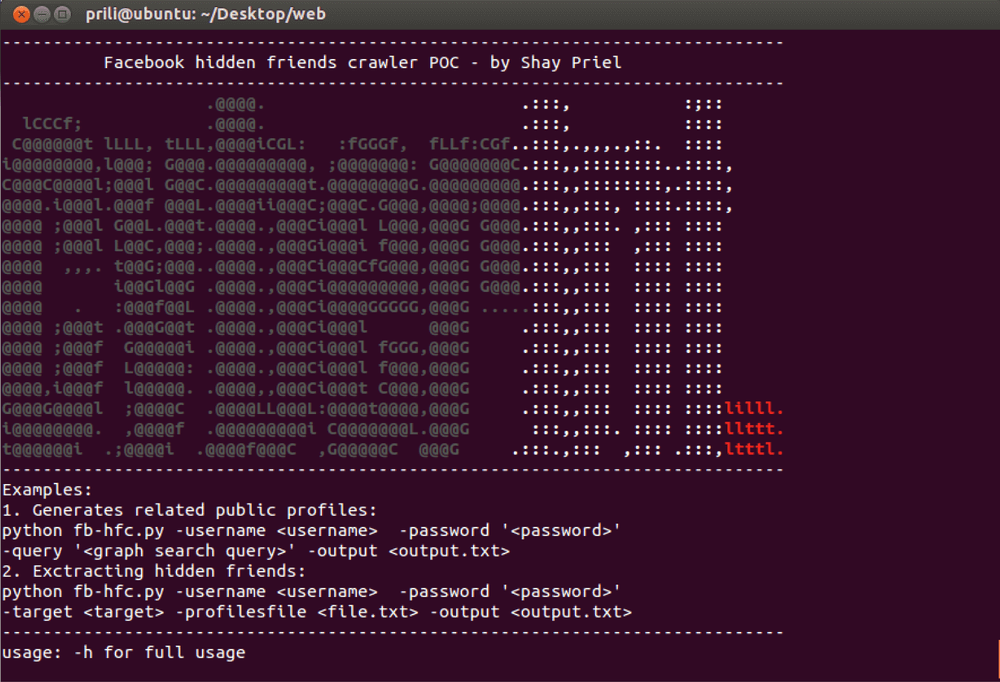

This, in turn, presents threat actors with alluring new attack vectors, particularly considering that the car industry has a spotty record with its software security. Case in point, in 2019 a software engineer identified a series of vulnerabilities in the car system known MyCar, which allows hackers to see GPS data, remotely locate cars, unlock them, and even start them up. The engineer, known as Jmaxxz, found SQL injection and direct object references vulnerabilities, that could allow attackers to send commands to affected vehicles. As if that weren’t enough, the researcher also found that the system contained hard-coded administrator credentials, which could grant access to its company’s backend data.

The system, which is rebranded and distributed to multiple companies including Kia, was estimated to affect around 60,000 cars. The failure in quality assurance to the project – in detecting the vulnerable systems before going to the market, could also have compounding ripple effects beyond just impacting the end-user.

True, 60 thousand is not a massive number in the grand scheme of things when considering that 80 million new vehicles were sold in 2020, but it is definitely an indication of the potential risks. So, while the MyCar incident has limited reach, it does illustrate a prevailing problem in the industry – car manufactures’ heavy reliance on third-party and open-source programs, coupled with often inadequate testing procedures.

Playing devil’s advocate for a moment, Toyota are likely taking precautions against these issues. Not for nothing they’ve gained a legendary reputation for reliability, due in part to generally taking their time to implement new technologies in their cars until they are proven. Furthermore, Toyota’s cars presumably have mechanical/electric fail-safe redundancies to prevent remote exploitation of critical systems.

New cyber security standards are also finally being introduced to mitigate these risks. For example, ISO/SAE 21434 provides specifies engineering requirements for cybersecurity risk management regarding electrical and electronic systems in vehicles, including their components and interfaces. But time will tell if they are sufficient, especially since cars are more and more technology-embedded; So much so that the recent global chip shortage dramatically hit car manufacturing. Toyota for example recently announced that it had to cut global production by 40% in September because of this.

And it’s worth noting that due to various reasons such as massive cost and logistical challenges, its particularly hard for car manufactures to resolve this problem. Manufactures are also understandably reluctant to introduce new chip designs into their cars when failures can endanger lives. But, as result this forcing them to use outdated and possibly more vulnerable silicon.

There are simply too many players and moving parts to accurately predict who, what and how will be exploited. As vehicles are becoming increasingly more connected, car manufactures are expected to link more and more core features to shut-off switches in order to monetize them in subscription plans, if recent developments are any indication.

And as history has taught us, threat actors are nothing but ingenious, and are painfully adapt in identifying unknown or overlooked vulnerabilities. Furthermore, they have no qualms in taking any measure necessary to do so with little regard to their victims. For instance, should an APT track the GPS data of delivery vehicles, it could hijack shipments on-route or attack warehouses following deliveries. Alternatively, they could shut-down fleets and hold them for ransom. One method that could be exploited is manipulating vehicles’ sensor data to forcibly activate emergency safety systems, essentially rendering the car undrivable.

With the retail industry for example, downtime of a single day may cause millions in losses . Not to mention other financial impacts such as customer churn and stock price drops. And with the car industry being global with a highly complex supply-chain, just in 2021 there have been over 800 reported automotive cyber incidents.

It’s easy to dismiss Toyota’s move as a simple cynical money-grab move, but as the entire automotive business becomes more interconnected, so do the risks; and subsequently so should be the counter measures taken by companies. On a high-level, both the car industry and different sectors should prioritize vehicle cybersecurity; this can be done amongst other things, by pushing for better security standards, as well as more transparency when in comes to wide-impacting shifts concerning vehicles’ core features.

On a more immediate level, companies should allocate resources for risk assessment – mapping how such threats may impact them and how to mitigate these. Companies’ security teams should also implement tools and systems to detect and monitor Indicators of Attack (IOA) and Indicators of Compromise (IOC) pertaining to their car fleets. Anything in the lines of unusual high data-traffic and/or anomalous errors from their car fleets.

Fill in your business email to start