The Cyberint Research Team work round the clock to unearth the latest threats to SMBs and enterprises. They are on top of the latest TTPs and monitor rising threat groups, malwares and trends.

September 2023 Update at the bottom

Responsible for a number of infamous ‘big game hunter’ ransomware attacks and believed active since at least 2019, the ransomware threat group dubbed ‘CL0P‘ is thought to be a Russian-language cybercriminal gang and have been widely reported as associated with, or their malware adopted by, other cybercriminal groups including ‘FIN11’, a part of the larger financially-motivated ‘TA505’ group, and ‘UNC2546’.

Fun Fact: The word clop comes from the Russian word “klop,” which means “bed bug,” a Cimex-like insect that feeds on human blood at night (mosquito).

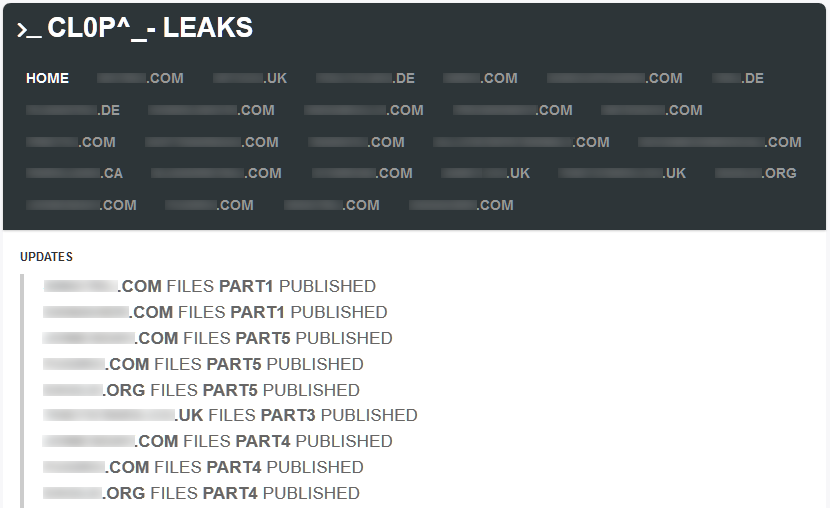

Utilizing common ‘steal, encrypt and leak’ tactics as employed by most big game hunter ransomware groups, victims failing to meet their ransom demands are promptly ‘named and shamed’ on ‘CL0P^_- LEAKS’, the group’s Tor-hosted leak site (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – CL0P Leak Site (Tor)

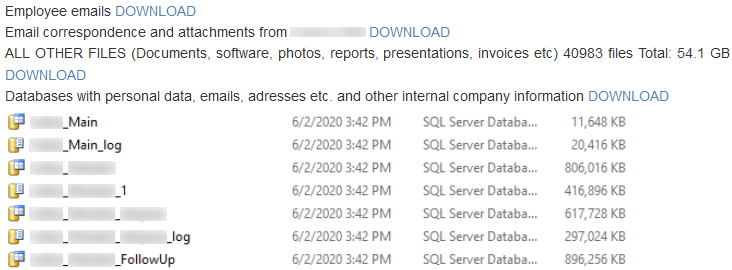

Typically these leaks include document excerpts and/or screenshots as ‘proof’ of compromise (Figure 2) followed by the periodic release of stolen data sets until such time that either the victim capitulates or all stolen data has been leaked.

Figure 2 – Example data leak

Consistent with many big game hunter ransomware campaigns, target organizations do not appear to belong to any specific industry or region and are more than likely selected based on being vulnerable to some known vulnerability and/or having the ability to pay a substantial ransom.

Furthermore, and as expected of many Russian-language threat groups, organizations within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) are seemingly precluded from attack.

Having previously targeted high-profile organizations including a Fortune 500 company and a multi-billion (US) dollar law firm, recent victims include a multinational household name within the oil and gas industry, a UK-based logistics company and numerous higher-education establishments.

Whist CL0P are thought to make use of broad malicious email (malspam) campaigns to identify potential corporate victims, recent evidence suggests that vulnerabilities in public-facing infrastructure are being exploited to gain a foothold within a victim network.

The prevalence of this exploit and intrusion tactic, and its successfully utilization by various big game hunter ransomware gangs, reinforces the need for organizations to take patch management seriously so as to minimize the window of attack for any identified vulnerability.

Notably of late, CL0P have utilized this tactic in the targeting of organizations using a vulnerable version of ‘Accellion FTA’, a file transfer appliance. As such, following vulnerabilities have reportedly been exploited to gain access to victim data as well as potentially pivoting into victim networks:

In the case of malspam campaigns, the group are thought to send their initial lures during the working week to ensure that the recipient is able to view the email and potentially infect themselves. Conversely, the network intrusion and ransomware deployment phases are reportedly conducted around the weekend in an attempt to minimize the chance of detection as well as potentially increasing the success of the encryption phase given that a lot of corporate data would be under-utilized and therefore not ‘locked’ open.

Finally, likely in an attempt to ‘cascade’ their ransomware threat and target other organizations, CL0P malspam campaigns have been observed as using data stolen from existing victims. As such, customers, partners or vendors of any victim organization could potentially be targeted with incredibly convincing email lures, especially if the group were to infiltrate and send malicious email lures from the original victim’s email server.

Although the initial infection vector may differ from one victim to another, CL0P’s objectives upon network intrusion remain consistent: the exfiltration of sensitive and valuable data prior to encryption in order to exert maximum pressure on victims and encourage prompt payment of ransom demands.

Likely commencing with a thorough reconnaissance phase, data stolen by the group typically includes customer, employee and financial records, likely of value to fraudsters, as well as sensitive emails, documents and intellectual property that could be damaging in the hands of competitors or when shared publicly.

In addition to the wholesale theft of data from file servers and network storage devices, a task made all the easier by the recent exploitation of file transfer appliances that already contain a wealth of data, CL0P have repeatedly demonstrated their ability to gather large data stores including those used by database and email servers.

Having exfiltrated any potentially valuable data, a victim specific ransomware threat is deployed by and commences a preparatory phase in which services related to various applications, such as backup software and database servers, are stopped using the Windows net.exe command line utility to allow ‘open’ or ‘locked’ data to be encrypted, for example:

cmd.exe /C net stop BackupExecAgentBrowser /yAdditionally, a number of application tasks are forcibly terminated, as specified by the /F using the Windows taskkill.exe command line utility, for example:

cmd.exe /C taskkill /IM powerpnt.exe /FGiven that Windows provides functionality to create point-in-time backup copies of data through the Volume Shadow Copy Service (known as VSS), it is common for malware and ransomware authors to utilize the VSS administrative tool vssadmin.exe to delete any existing shadow copies and prevent data restoration:

vssadmin delete shadows /all /quietIn CL0P’s case, both the typical ‘delete’ operation has been observed as well as the ‘resize’ operation which reduces the amount of disk space allocated to shadow copy storage, for example:

cmd.exe /C vssadmin resize shadowstorage /for=c: /on=c: /maxsize=401MBIn addition to the resize operation resulting in insufficient disk space being allocated for the volume of file changes occurring during the encryption phase, a high volume of disk input/output operations can result in the VSS process being overwhelmed and the snapshot being deleted anyway.

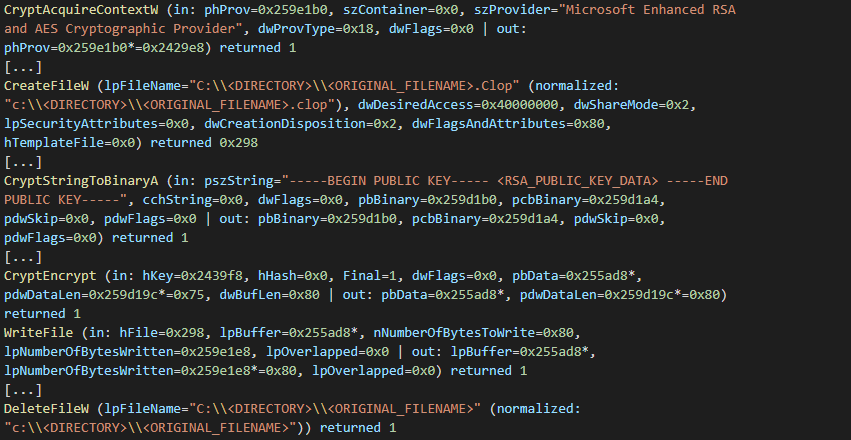

Based on the use of a ransomware binary specific to the victim, including an embedded 1024-bit RSA public key and a unique ransom note, multiple processing threads are spawned to read each target file into memory, encrypt the data using the Windows CryptoAPI and then writing this encrypted data to a new file before the original is deleted (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Encryption process (abridged) followed by original file deletion

The resulting encrypted files, in addition to having a Clop^_- marker within the file (Figure 4), will have a filename extension that is typically some variation on the CL0P name such as .Cllp, .Clop or .Cl0p.

Figure 4 – Encrypted file marker

Created on a per victim basis and encrypted within the victim-specific ransomware sample, ransom notes are typically saved to each folder containing encrypted files and are named to attract attention from the victim, for example,Cl0pReadMe.txt or README_README.txt.

Having informed the victim of the network intrusion and data encryption, the ransom note typically contains victim-specific details of specific exfiltrated data as well as warning that non-compliance with the group’s demands will result in data being published to their Tor-based leak site.

Unlike some groups and setting out an exact ransom sum and a cryptocurrency address for payment, CL0P provide multiple contact email addresses as well as, more recently, a link to an online chat feature on their Tor hidden service, that can be used to enter into ‘negotiations’.

Based on previous campaigns, the email addresses provided within these ransom notes are hosted on privacy-focused email providers such as ProtonMail or Tutanova, and therefore provide some layer of anonymity to those behind the attack.

Following the vulnerabilities that were found in the MOVEit transfer software. Cl0p Ransomware announced that they would be releasing hundreds of new victims. By June 20th they had released 100+ victims, including Norton LifeLock and UCLA. On June 27th they released another list of 10 further victims such as Kirkland, Delta Dental, Siemens Energy and more. And by July they showed no sign of slowing down with more than 515 victims claimed, and more being released on a weekly basis

The US Gov’t has now placed a $10M Bounty on Cl0p Ransomware’s head as the MOVEit Fallout Continues.

The latest victims to be revealed include Michigan State University, Forever 21, Tesla and Stamford.

Below are the current CVEs that Cl0p is exploiting:

| Type | Value | Last Observation Date |

|---|---|---|

| SHA256 | e90bdaaf5f9ca900133b699f18e4062562148169b29cb4eb37a0577388c22527 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 55e070a86b3ef2488d0e58f945f432aca494bfe65c9c4363d739649225efbbd1 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 37546b811e369547c8bd631fa4399730d3bdaff635e744d83632b74f44f56cf6 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 555964b2fed3cced4c75a383dd4b3cf02776dae224f4848dcc03510b1de4dbf4 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | fd7cbadcfca84b38380cf57898d0de2adcdfb9c3d64d17f886e8c5903e416039 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 76f860a0e238231c2ac262901ce447e83d840e16fca52018293c6cf611a6807e | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 0b3220b11698b1436d1d866ac07cc90018e59884e91a8cb71ef8924309f1e0e9 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 0ea05169d111415903a1098110c34cdbbd390c23016cd4e179dd9ef507104495 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 110e301d3b5019177728010202c8096824829c0b11bb0dc0bff55547ead18286 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 1826268249e1ea58275328102a5a8d158d36b4fd312009e4a2526f0bfbc30de2 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 2413b5d0750c23b07999ec33a5b4930be224b661aaf290a0118db803f31acbc5 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 2ccf7e42afd3f6bf845865c74b2e01e2046e541bb633d037b05bd1cdb296fa59 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 348e435196dd795e1ec31169bd111c7ec964e5a6ab525a562b17f10de0ab031d | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 387cee566aedbafa8c114ed1c6b98d8b9b65e9f178cf2f6ae2f5ac441082747a | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 38e69f4a6d2e81f28ed2dc6df0daf31e73ea365bd2cfc90ebc31441404cca264 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 3a977446ed70b02864ef8cfa3135d8b134c93ef868a4cc0aa5d3c2a74545725b | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 3ab73ea9aebf271e5f3ed701286701d0be688bf7ad4fb276cb4fbe35c8af8409 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 3c0dbda8a5500367c22ca224919bfc87d725d890756222c8066933286f26494c | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 4359aead416b1b2df8ad9e53c497806403a2253b7e13c03317fc08ad3b0b95bf | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 48367d94ccb4411f15d7ef9c455c92125f3ad812f2363c4d2e949ce1b615429a | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 58ccfb603cdc4d305fddd52b84ad3f58ff554f1af4d7ef164007cb8438976166 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 5b566de1aa4b2f79f579cdac6283b33e98fdc8c1cfa6211a787f8156848d67ff | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 6015fed13c5510bbb89b0a5302c8b95a5b811982ff6de9930725c4630ec4011d | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 702421bcee1785d93271d311f0203da34cc936317e299575b06503945a6ea1e0 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 769f77aace5eed4717c7d3142989b53bd5bac9297a6e11b2c588c3989b397e6b | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 7c39499dd3b0b283b242f7b7996205a9b3cf8bd5c943ef6766992204d46ec5f1 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 93137272f3654d56b9ce63bec2e40dd816c82fb6bad9985bed477f17999a47db | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 98a30c7251cf622bd4abce92ab527c3f233b817a57519c2dd2bf8e3d3ccb7db8 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 9d1723777de67bc7e11678db800d2a32de3bcd6c40a629cd165e3f7bbace8ead | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | 9e89d9f045664996067a05610ea2b0ad4f7f502f73d84321fb07861348fdc24a | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | a1269294254e958e0e58fc0fe887ebbc4201d5c266557f09c3f37542bd6d53d7 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | a8f6c1ccba662a908ef7b0cb3cc59c2d1c9e2cbbe1866937da81c4c616e68986 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | b1c299a9fe6076f370178de7b808f36135df16c4e438ef6453a39565ff2ec272 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | b5ef11d04604c9145e4fe1bedaeb52f2c2345703d52115a5bf11ea56d7fb6b03 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | b9a0baf82feb08e42fa6ca53e9ec379e79fbe8362a7dac6150eb39c2d33d94ad | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | bdd4fa8e97e5e6eaaac8d6178f1cf4c324b9c59fc276fd6b368e811b327ccf8b | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | c56bcb513248885673645ff1df44d3661a75cfacdce485535da898aa9ba320d4 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | c77438e8657518221613fbce451c664a75f05beea2184a3ae67f30ea71d34f37 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | cec425b3383890b63f5022054c396f6d510fae436041add935cd6ce42033f621 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | cf23ea0d63b4c4c348865cefd70c35727ea8c82ba86d56635e488d816e60ea45 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | d477ec94e522b8d741f46b2c00291da05c72d21c359244ccb1c211c12b635899 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | d49cf23d83b2743c573ba383bf6f3c28da41ac5f745cde41ef8cd1344528c195 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | daaa102d82550f97642887514093c98ccd51735e025995c2cc14718330a856f4 | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | e8012a15b6f6b404a33f293205b602ece486d01337b8b3ec331cd99ccadb562e | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | ea433739fb708f5d25c937925e499c8d2228bf245653ee89a6f3d26a5fd00b7a | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | ed0c3e75b7ac2587a5892ca951707b4e0dd9c8b18aaf8590c24720d73aa6b90c | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | f0d85b65b9f6942c75271209138ab24a73da29a06bc6cc4faeddcb825058c09d | Nov 15, 2023 |

| SHA256 | fe5f8388ccea7c548d587d1e2843921c038a9f4ddad3cb03f3aa8a45c29c6a2f | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://hiperfdhaus.com | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://jirostrogud.com | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://qweastradoc.com | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://qweastradoc.com/gate.php | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://connectzoomdownload.com/download/ZoomInstaller.exe | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | https://connectzoomdownload.com/download/ZoomInstaller.exe | Nov 15, 2023 |

| Url | http://guerdofest.com/gate.php | Nov 15, 2023 |

net.exe, taskkill.exe and vssadmin.exe.First Published in November 2021

Fill in your business email to start